Air is Kin Health Diary Symptoms Weekly Tracker

The AIK Health Diary Symptoms Weekly Tracker is for people who prefer more structured and direct questionnaires to answer. These questions have been reviewed by community advocates, academics, and healthcare professionals to make sure that they are relevant for comfortably recording the lived experience associated with air pollution exposure.

Air is Kin

The AIK Health Diary Symptoms Weekly Tracker is for people who prefer more structured and direct questionnaires to answer. You can respond to the questions in this weekly tracker in whichever form is most convenient for you to the best of your ability.

These questions have been reviewed by community advocates, academics, and healthcare professionals to make sure that they are relevant for comfortably recording the lived experience associated with air pollution exposure. Weekly recording always you to devote time without a heavy burden that may come with daily symptom tracking.

To download a pdf copy of this please use this link or read via the slideshow viewer on this page.

To learn more about self documenting your air pollution related health concerns in a health diary, read the Air is Kin Health Diary Info Guide.

Further Reading

Air is Kin Health Diary Info Guide

The AIK Health Diary Info Guide provides the purpose, use cases, and methodology for starting your own health diary that captures your air pollution related health symptoms. We recommend sharing this document and discussing it with others who share your concerns about documenting their health or may want to assist you.

Air is Kin

We have recognised, through experience with communities and working alongside doctors, that the most accessible starting point for healing and justice in air pollution is empowering people to document their changes in health as soon as they start to feel concerned. People often do this through varied conversations within their community and the notes made on any material available to them at the time without any indication of what will be useful for their self-advocacy.

The AIK Health Diary Info Guide provides the purpose, use cases, and methodology for starting your own health diary that captures your air pollution related health symptoms. We recommend sharing this document and discussing it with others who share your concerns about documenting their health or may want to assist you.

To download a pdf copy of this please use this link or read via the slideshow viewer on this page.

To get more structured questions and formatting for routinely documenting in a health diary, read the Air is Kin Health Diary Symptoms Weekly Tracker.

Further Reading

Colonization, U.S. Property Law, and the Right to Pollute

This Essay explores the relationship between colonization, U.S. property law, and the right to pollute. It argues that the foundation of U.S. property law is rooted in colonization, used as a tool to genocide Native Peoples of Turtle Island and colonize Indigenous Land.

Air is Kin

This essay has been written by Dr Grace L. Carson for the Air is Kin project. It is an Argument for a Decolonial, Abolitionist Framework in Environmental Protections.

We asked Dr Grace Carson, who is a Land Rights scholar to write a research essay tying the concept of "right to pollute" to the systemic separation of Indigenous Peoples of Turtle Island from the Ancestral Lands. This is to help us understand the epistemological pathways and narrative roots of current laws and policies that permit our Air to be polluted. The essay also provides a historical lens to the struggles against contamination, helping advocates see the broader factors that contribute to Air pollution, such as land ownership.

Whilst the essay centres Turtle Island, Grace highlights the epistemological and structural origins of land law in North America to be tied to Britain. This means that how British People are taught to imagine their relationship with the Land affects the policies that make air pollution legal to this day. British law and its conceptualisation of Land has affected communities beyond

One of the main learnings from this piece is that once the Land is imagined as an object that can be owned, bought, and sold, it creates the mental pathways to legally justify their abuse and destruction.

Further Reading

Vital Signs Exhibition: Context & Learnings

Here we share some context and learnings from exhibiting work from Air is Kin in the Vital Signs exhibition at the Science Gallery London from 2024-25.

“I think the idea that the environment is not just something around you, but has got to be treated as probably a friend, or maybe a living being, that sort of put things a little bit more into perspective, because it’s a lot harder to desecrate something that is actually a living being.”

- Exhibition attendee

Context

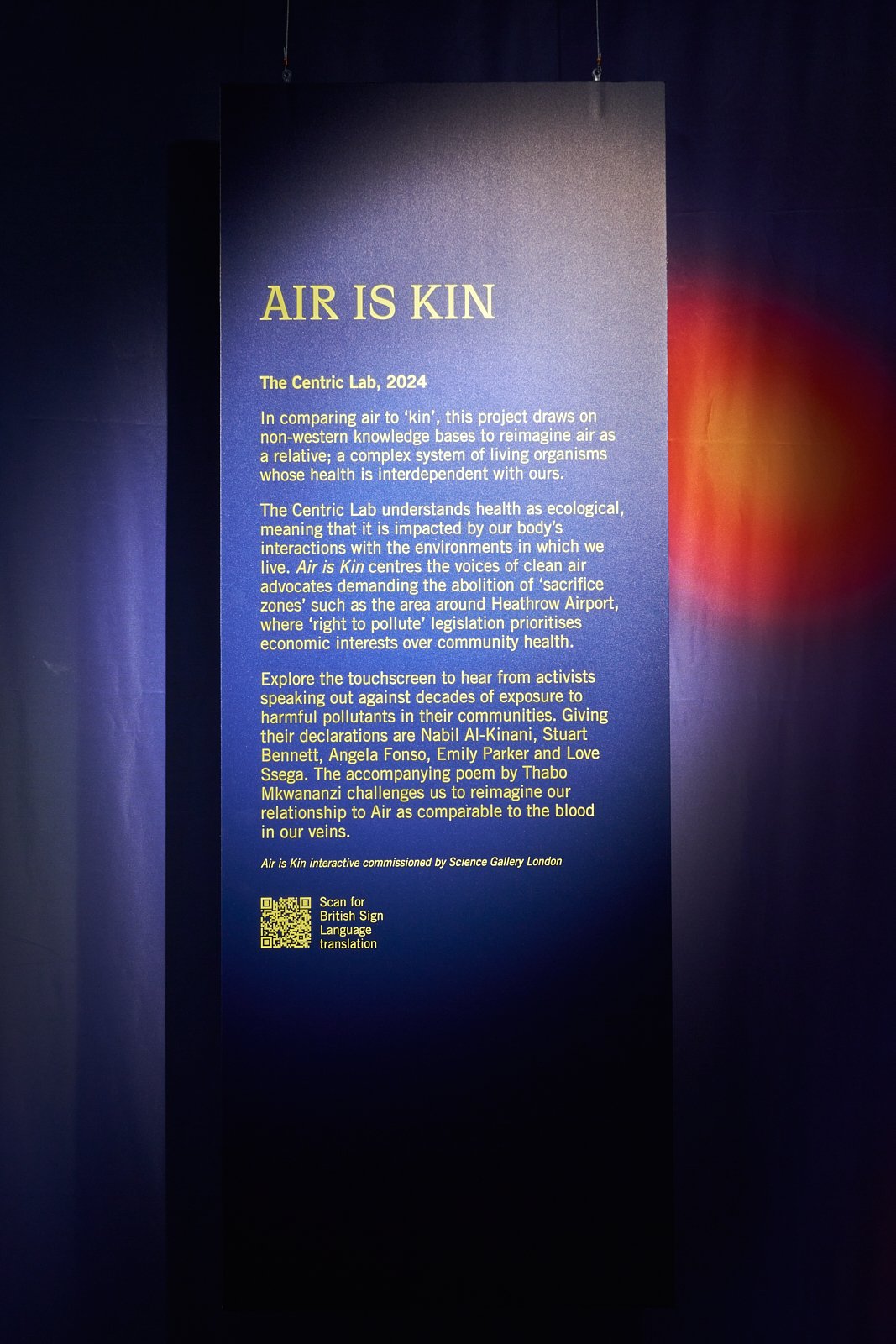

Centric Lab were invited to be part of a special exhibition at the Science Gallery London called VITAL SIGNS: Another World is Possible.

The exhibition brought together artists, designers and researchers to explore how the health of the natural world - from our waterways to our atmosphere and the ocean floor - is intimately connected to our own health and wellbeing.

Centric Lab exhibited an interactive, data-supported, piece of work related the Air is Kin project. A digital touchscreen allowed visitors to explore 6 locations in England and through headphones hear first-person narration accounts of activists, doctors, and campaigners working in those locations. The digital screen hosted geographic maps from the six locations showing analysis results from the Urban Sacrifice Zones work. This work showed which MSOA region had a high intersection between deprivation and sites of industrial air pollution. Data was used from the English government’s own Index of Multiple Deprivation and the National Atmospheric Emissions Inventory. Through data, first person accounts, and displayed information visitors could learn more about the systemic forces that result in some areas being more polluted than others and what changemakers are trying to do about it.

-

Carrying momentum from previous conversation, on Jan 2024, in an email to Jen Wong, Head of Programming at Science Gallery London, Araceli from the Centric Lab team proposed a collaboration between Centric and SGL with the following:

“The purpose would be to use this opportunity to disseminate the work within the Declaration for Air and increase awareness of how the air that we breathe is not actually air anymore. Therefore our campaigning for clean air, should [be] asking for Air to be healed and [Being-ness] restored.

-

A microbiological and ecological understanding of air

The introduction to "sacrifice zones"

Restoring our relationship with Air and Breath

Assimilative Capacity and how that creates "right to pollute policies"

The links between Air and Planetary Health

-

We could ask Thabo Mkwananzi, who was the poet and artist that we used to write the Declaration to speak on the relationship between the AIr, Breath, and Planetary Health

We could also create [an] "Air as Kin" mini-programme that can be a combination of children workshops, lectures, and Q+A.

We can do an exhibit [with] the data visualisations for "sacrifice zones" that are also narrativised with lived experience stories.

Finally, there is an opportunity to print out the Declaration and have it for people to take”

This proposition was to carry on from the momentum of the Declaration for Air. Science Gallery London were developing the Vital Signs (VITAL SIGNS: another world is possible, new exhibition and events from 13 November 2024 — Science Gallery London) exhibition and the fit made sense with the goals of what Araceli proposed.

-

Science Gallery London: Science Gallery London

“Science Gallery London is a place to grow new ideas across art, science and health. A part of King’s College London, we’re the university’s flagship public gallery situated on King’s Guy’s Campus next to London Bridge station.

As a university-based gallery, we try to spark new ways of thinking about some of the most complex contemporary challenges we face. The work we share here emerges from dialogue and collaborations between communities of artists, academics, students, young people, activists, local organisations and more.

The Gallery brings together a breadth of perspectives to shape and share a programme of exhibitions, residencies, workshops, open discussions, festivals, performances and live research.

Entry to all of our exhibitions and events is free. Our doors are open for you to explore”

As mentioned, this collaboration was a pilot in applying our work in a cultural worker setting that is accessible to the general public as opposed to the majority of our work which is online in reports or through learnings journeys.

10PM Studio: 10PM

10PM is a design and technology studio based in London founded by Rob Prouse and Tom Merrell.

We design and build brand identities, websites, digital interfaces, e-commerce and online platforms for clients in the cultural and creative sector.”

SGL contracted 10PM to create the proposed data visualisation.

-

Science Gallery London provided a stipend fee to cover some costs whilst the majority of the Air is Kin work is funded by Guy’s & St. Thomas’s Foundation through Impact on Urban Health.

-

Declaration for Air: A Declaration for Air — CENTRIC LAB

One of the biggest drivers of engaging with this work was to continue the momentum of the Declaration for Air, the result from a session on 11th October 2023, where 14 people ranging from the fields of medicine, policy, law, abolition, science, data science, economics, and art gathered to declare our right to access AIR.

Air is Kin: Air is Kin — CENTRIC LAB

The mission of the [Air is Kin] project is to move towards the abolition of “Right to Pollute” policies and to facilitate healing pathways for communities impacted by air pollution. This project and study are meant to create a starting point for the abolition of the right to pollute policies, which are having a continual devastating effect on both planetary and human health.

OUTPUTS

Multimedia Installation

Friday Late Event

-

Centric Lab exhibited an interactive, data-supported, piece of work related to the Air is Kin project. A digital touchscreen allowed visitors to explore 6 locations and 6 first-person audio witness statements from advocates, doctors, practitioners, and campaigners in England. The digital screen hosted geographic maps from the six locations showing analysis results from the Urban Sacrifice Zones work.

This work showed which Middle Layer Super Output Area (MSOA) region had a high intersection between deprivation and sites of industrial air pollution. We used MSOAs because they are a geographic size close to the scale of a ward but closer to how one might associate with their area. Data was used from the English government’s own Index of Multiple Deprivation and the National Atmospheric Emissions Inventory. Through data, first person accounts, and displayed information visitors could learn more about the systemic forces that result in some areas being more polluted than others and what changemakers are trying to do about it.

The first-person witness statements were from:

Angela Fonso, Clean Air for Southall & Hayes.

Nabil Al-Kinani, Brent based built-environment professional and strategist.

Stuart Bennett, Merseyside based campaigner for Save Rimrose Valley.

Dr. Emily Parker, Newcastle based GP.

Love Ssega, South London campaigner, musician, producer and artist.

The installation also featured a poem by Thabo Mkwananzi [pictured in the right of the photo above].

-

SGL hosted a variety of events around the Vitals Signs exhibition over the course of the November to May timeframe. The March Lates included a viewing of Black Corporeal (Breathing by Numbers) by Julianknxx followed by a discussion and Q&A with Julianknxx, Araceli Camargo and Professor Ioannis Bakolis, chaired by Karin Woodley.

Breathing by Numbers is anchored by the voice of Rosamund Adoo-Kissi-Debrah, who traces her journey to officially acknowledge air pollution as a cause of death of her 9-year-old daughter, Ella Adoo-Kissi-Debrah. This moving film explores the stark realities of environmental poverty as experienced by Black and working-class people in London, while honouring a culture of resilience and perseverance.

Reflections on event

The crowd had a mix of lived experience, health practitioners, planning, students, and general locals. There was first some discussion involving themes from the video. There were some key themes and quotes from what Julian said that felt impactful:

What does it look like to be alive today?

What does it look like in the future?

“If you aren’t living your imagination, you're in someone else’s.”

Imagination has structure.

“The joy comes after the work.”

Find your medium for carrying big ideas, then listen.

[Art as a] language for things you can’t explain.

The questions from the Q&A mostly covered aspects of engaging with the realities of structural pollution and people’s role in change and justice in addition to questions to Julian regarding the artistic directions of the video.

From the event as well as talking to Julian and Araceli afterwards, there is definitely space needed for someone like Julian who is arguably a culture and cultural worker in different cases to propose these sorts of questions and provocations in the health and environmental justice space, particularly in an accessible space to the public.

FEEDBACK FROM VISITORS

“Oh, the part about air, I really liked the part where they were following one group and they were talking about how air is a part of us and how we are supposed to have a symbiotic relationship with that, like air is life, I really liked that one.”

“Yes, if the air is sick, then we are sick, and I think that connects to a lot of things that are happening. I feel like it’s out of sight, out of mind, but I feel like a lot of people don’t want to recognise the changes that are happening. They think like “oh, landfill, it’s just a part of us”, or the things that we find in the ocean. At the end of the day, if the earth is dying, and we are made of the earth, then at the end of the day we are going to end up dying. So I think that was really interesting to see in a more expressive way vs. just like media.”

“I think the idea that the environment is not just something around you, but has got to be treated as probably a friend, or maybe a living being, that sort of put things a little bit more into perspective, because it’s a lot harder to desecrate something that is actually a living being.”

Charlotte Russell worked with a PhD student Megan Lawrence on some audience evaluation in Vital Signs as part of some psychology research around memory and recall. They asked people to recall aspects of the exhibition at different time points following a visit. The following are quotes or summaries of quotes from the data shared with SGL:

Q - (what was most memorable?):

Several respondents found the visualisations and stories, particularly about Angela Fonso and the Southall campaign, memorable and relatable to their own life.

Another respondent found the term urban sacrifice zones to be a new term that made a lot of sense once introduced.

Q - From research participants – (Has anything stayed with you?):

“The part of the exhibition about the air pollution in Southall has stayed with me as I remember quite well how serious the lady on the video we watched (Angela) was about the danger it was putting her child in.”

Upon further questioning on what stayed with people, there were a few key insights:

Urban sacrifice zones are not common terminology, but people really find the concept relatable, especially when the data relates to their area and the descriptions reflect their upbringing. The term especially appealed to people who were interested in social justice as a cause.

Angela Fonso’s story with Southall impacted people because it drew their attention to relatable lived experiences.

The “personification” of Air stayed with some people. Even though we aren’t actually trying to make Air into a citizen or person, we are encouraging people to respect the relationship between people and Air.

REFLECTIONS

These are just a few reflections in the form of provocations that came from having completed this work:

Art exhibitions can be soft pathways to change long-standing narratives, establish new lores, which in turn can change societal norms.

Within the clean air movement, there is a rightful tendency to go straight to policy change. However, laws and policies are heavily influenced by societally accepted lore. This exhibition allows us to gauge how people respond and enact new lores.

How can cultural workers (like gallery curators, universities) leverage their resources as being some part of infrastructure to complement researchers and culture workers in supporting communities with health reparations?

How can installations like the Air is Kin/Vital Signs be used as tools in how communities approach health reparations?

What mechanisms need to be in place to encourage and enable communities interested in health reparations to propose and lead the work in these spaces?

A Case for Health Reparations

We present pathways, philosophies, and strategies for community-led healing to safeguard against air pollution.

A Declaration for Air

On 11th October 2023, 14 people, ranging from the fields of medicine, policy, law, abolition, science, data science, economics, and art gathered to declare our right to access AIR.

Air is Kin

On 11th October 2023, 14 people ranging from the fields of medicine, policy, law, abolition, science, data science, economics, and art gathered to declare our right to access AIR.

To download a pdf copy of this Declaration for Air please use this link.

Further Reading

Who are AIR?

In current conversations about air pollution, we have grown accustomed to perceiving Air as simply the absence of pollutants. However, Air is vastly more than this. We asked Dr Jake Robinson, who is a microbial ecologist to provide an understanding of Air that is more robust, spiritual, and scientific.

Air is Kin

“Air” has many faces.

From a Western science perspective, air commonly refers to the mixture of gases that make up the Earth's atmosphere. This includes gases like nitrogen, oxygen, carbon dioxide, and trace amounts of other gases. In a human context, air represents the mixture of gases we breathe to sustain life, which primarily consists of oxygen and nitrogen.

In many Indigenous cultures, the natural elements, including air, hold deep spiritual, cultural, and ecological significance. The elements of nature, including air, are often associated with spirits or deities. Air may be seen as a source of life and a carrier of messages. Air is vital for aerobic life, hence the term breath of life.

The act of breathing is connected to the life force, and rituals and ceremonies may involve breathing practices. Indigenous cultures also emphasise a deep interconnection with the natural world, and air, as one of the natural elements, is considered a fundamental part of this web of life.

Air has a dynamic ecology. Indeed, it’s challenging to imagine a more dynamic medium. One of the fundamental ecological processes in the atmosphere is gas exchange. We inhale the exhalations of plants and diverse microorganisms as they inhale ours––the most magnificent occurrence of unconscious reciprocity.

Cyanobacteria in the ocean gave rise to much of the oxygen in the atmosphere, and some now think phage viruses inoculated these bacteria with the genetic machinery required to photosynthesise. So, in addition to plants, we have microbes (even viruses) to thank for the air we breathe.

The air contains diverse microbial communities of bacteria, viruses, archaea, algae, fungi, protozoa and tiny animals, along with pollen, organic compounds and spores galore. Microbes and their by-products in the air play roles in nutrient cycling, pollination, and cloud formation, and influence the health of humans and non-humans alike.

The air contains diverse microbial communities of bacteria, viruses, archaea, algae, fungi, protozoa and tiny animals, along with pollen, organic compounds and spores galore. Microbes and their by-products in the air play roles in nutrient cycling, pollination, and cloud formation, and influence the health of humans and non-humans alike.

The dynamic ecology of air is essential for the migration and dispersal of various life-forms, including birds, insects, microbes and plants. Air currents play a vital role in these movements, influencing the distribution of species and the establishment of new communities and ecosystems.

Air currents erode, transport and deposit, eternally shaping the planet’s landscapes. But it’s not just physical or chemical entities (organisms, soil particles, odours) that air transports.

Air molecules also play a role in transmitting sound. The vibration of air molecules and their ability to pass on these vibrations to neighbouring molecules is how sound energy is transmitted through a given space. Air also carries rich organic odours that nourish our senses and allow bees and other insects to locate flowers, thus instigating a great multi-species collaboration, a cycle that affects all of us.

Some estimate that with each breath, we inhale more air molecules (25 sextillion or 25,000,000,000,000,000,000,000) than there are grains of sand on all the world’s beaches. We each inhale up to 15,000 litres of air every day, exposing our ‘walking ecosystems’ to an array of invisible biodiversity.

We often speak of air in terms of its quality. Indeed, high levels of pollution and pathogens fill the air in many places and cause (preventable) diseases. This happens when we fail to respect air. It happens when we fail to foster kinship with the natural world; when we “bite the hand that feeds us”.

It can be challenging to define ‘healthy air’. However, a good starting point is promoting air characterised by very low pollution and pathogen levels and the presence of beneficial microbiota and other biogenic compounds, such as phytoncides.

Evidence shows an environmental microbiome with specific characteristics can be considered ‘health-promoting’. For instance, higher alpha diversity, along with immune-priming taxa, such as Gammaproteobacteria and other functionally important microbial ‘old friends’ (e.g., some species of Streptomyces, Lactobacilli, Bifidobacteria), have been shown to have salutogenic effects.

The microbiome of the air (the aerobiome) is primarily “fed” by the soil and vegetation. We can shape these airborne communities in beneficial ways through ecosystem restoration and practices that promote soil health.

Some estimate that with each breath, we inhale more air molecules (25 sextillion or 25,000,000,000,000,000,000,000) than there are grains of sand on all the world’s beaches. We each inhale up to 15,000 litres of air every day, exposing our ‘walking ecosystems’ to an array of invisible biodiversity.

“Healthy air” in this regard is not equally distributed. While air should nourish life, the substances it now carries have, in many cases, become a detriment to the wellbeing of humans and non-humans alike. Communities located near industrial facilities, transportation hubs, or areas with high pollutant emissions are more likely to experience poor air quality. These areas are often home to lower-income human communities that may not have the resources to relocate––and they shouldn’t have to.

The people who bear the brunt of air pollution are often those least responsible for tainting the air with the toxic chemicals and particles that drive the health issues.

Air should be a bestower of life, a cradle of existence. While it should nourish us, we have a responsibility to nourish it in return, through conscious reciprocity. This path requires an end to pollution and a new era of ecosystem restoration.

Further Reading

A Need For an Abolitionist Strategy

How governments arrive at air pollution policies and contamination allowances are dependent on science, governmental policies, and narratives that are culturally acceptable. It is also important to consider that currently policies and laws that protect polluters are all done without community consent. Therefore, in order for us to access air that is nourishing and clean, we have to employ an abolitionist strategy.

Air is Kin

This strategy was put together alongside our colleagues Dr Patrick Williams and Dr. Kavian Kulasabanathan, working with Araceli Camargo and Daniel Akinola-Odusola.

Brief History of the Right to Pollute

Defining

Pollution in English is generally defined along the lines of harmful substances introduced into the environment (compared with ‘contamination’). Ambiguity can emerge given that some substances have thresholds or ranges for which they cause harm or could be deemed to be ‘harmful’--and these thresholds and ranges can vary according to context. UK legislation defines ‘pollution’ in the Pollution Prevention and Control Act 1999, with updates in the Environment Act 2021, as:

(2) In this Act—

“activities” means activities of any nature, whether—

industrial or commercial or other activities, or

carried on on particular premises or otherwise,

and includes (with or without other activities) the depositing, keeping or disposal of any substance;

“environmental pollution” means pollution of the air, water or land which may give rise to any harm; and for the purposes of this definition (but without prejudice to its generality)—

“pollution” includes pollution caused by noise, heat or vibrations or any other kind of release of energy, and

“air” includes air within buildings and air within other natural or man-made structures above or below ground.

(3) In the definition of “environmental pollution” in subsection (2), “harm” means—

harm to the health of human beings or other living organisms;

harm to the quality of the environment, including:

harm to the quality of the environment taken as a whole,

harm to the quality of the air, water or land, and

other impairment of, or interference with, the ecological systems of which any living organisms form part.

The Right to Pollute is a societal framing and infrastructure that sees pollution as an inevitability of society, particularly by larger, high-consuming, industrial entities such as factories, construction, and transport. The Right to Pollute is not equitable both in how these larger entities are licensed to pollute more while individuals and households are more strongly encouraged to reduce pollution, sometimes by policy and law. In this framing, if you are perceived to contribute more to society, you have more rights on how much pollution you can afford to produce.

The legal history of Right to Pollute policies relies on what is referred to as “assimilative capacity,” a scientific concept that underpins the theory that environments can handle a specific amount of contaminants before harm occurs.

Considerations For Right to Pollute Policies

There is an innate understanding (or compromise) that Nature should endure a specific amount of damage before a recognition of harm is acknowledged.

Who is defining the meaning of “harm” in this case? It is not the Water, Air, or Land, nor is it the people that interact with them.

Can harm be defined or the threshold identified with accuracy? In other words, the thresholds of harm are arbitrary and driven by the cognitive framings of the scientists. Harm as a concept is quite personal and its threshold should be defined by those who the harm is being inflicted on, not the harmer.

Science without moral instruction can and does cause violence, as is the case of assimilative capacity. This term has been used to justify the pollution of our habitats as it gives the industry the ability to define what harm is, not the people nor the Nature they are damaging.

This perspective also erases the pathways of consent. The Beingness and Personhood of the habitats that are harmed are not taken into consideration. Therefore, these policies do not reflect their consent to harm as well as the consent of the People and other non–human Beings who live in the habitat. Their voices of what is “harm” are completely ignored or lost when they protest against the contamination.

Pay to Pollute

A financial settlement for pollution, whether court-mandated or out-of-court, might be less than the profits made by polluting and/or might not include a provision to stop polluting. Consequently, it is cheaper to continue making profits from pollution while paying financial penalties, in effect being an opportunity to pay in order to pollute. For example, Volkswagen’s financial viability was never in question despite having lied about emissions from their vehicles. The equations change if leaders of the polluter face personal fines or jail time–or if the financial penalties increase each time to the point that the polluter cannot afford to pay.

Carbon offsets or greenhouse gas offsets are a similar ‘pay to pollute’ principle. Whatever price an airline ticket or train ticket is, some people can afford it and some cannot. An increase in the ticket price, for offsets or a pollution clean-up fund or another mechanism, means that fewer people can afford the ticket, but many people still can. The more someone can afford to pay for a plane or train ticket, the more that person can afford to pay to pollute. Alternatives include investing in less polluting transportation over the entire life cycle alongside cultural and technological changes to support lifestyles requiring and desiring less travel, as long as the alternatives to travel do not create more life-cycle pollution.

See one UK survey https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123416000727

The Need

Based on the past studies, we have identified the following list of needs within the environmental justice movement.

The majority of the justice is centred around lawsuits which financially compensate communities affected, however the communities are still left with the poor health effects. Therefore, there is a need to look beyond lawsuits and into health reparation, health justice, and legal mechanisms for pollution prevention. What this looks like should be community specific, here are some examples:

Actions that prevent pollution to avoid adverse health impacts

Health centres that specialise in air pollution effects

Specialised research centres that look at healing techniques for those affected by air pollution.

Community led educational learning programmes on data, effects of air pollution, and key vocabulary related to clean air policies.

The centering on lawsuits rather than health justice, means that communities that live within proximity of an industrial site experience disproportionate levels of cardiovascular, respiratory, and educational disorders, as well as cancers, while lacking mechanisms to prevent pollution..

Whilst there is a lot of information on how air pollution creates disease, we are missing information on how air pollution reduces quality of life on a day-to-day basis. This includes identifying symptoms such as headaches, nausea, fatigue, nose bleeds which can reduce a person’s quality of life. Preventing them from engaging with family, friends and community, requiring more sick days which can affect household income, and generally feeling like home is a place of stress.

Symptoms are the only way that the lived experience is affected. We must also consider how people are affected by not being able to go outside, feeling unsafe in their home, worrying about the health of their loved ones, experiencing ecological death and changes to places that are ancestral, feelings of powerlessness and hopelessness.

Mental burden:

Currently in the UK the focus on clean air has been at the individual level (car use, type of car, cookers, and heating devices), this has erased the responsibility of industrial polluters

There are multiple top-down factors that contribute to individual choices, such as income, housing quality, living near roads vs green areas, owning or affording a flat, proximity to resources, and policies. Therefore, only focusing on individual choices creates more health and environmental inequities.

This project will therefore focus on industrial polluters, who are systemically creating environmental and health injustices.

Whilst there are great air pollution monitoring devices that are free and available to communities, there is still a need for more robust infrastructure at a community level. This is to prevent communities being gaslit, contributing to the momentum of environmental and health justice, and preventing industrial polluters from lying about the effects of air pollution.

Data literacy

Data collection methods that are cheap to free and backed up by science

Science and community collaborations to create justice based data analysis.

Community driven policy infrastructure

Environmental justice literacy to enable

A Need for an Abolitionist Strategy

The contamination of our air from industry is seen as a necessary output for economic growth, which we are told we need in order to provide society with necessary resources such as jobs, technology, comfort, and convenience. Due to this perceived value, industry is legally allowed to contaminate our air. To get to this point there needs to be systemic support. For example, the High Speed 2 (HS2) train is a high-speed railway line which is under construction in England, it has been given a narrative, driven by the government of environmental friendliness as it aims to be net zero and could reduce the need for air travel. However, on the ground it is a different reality, the construction itself, just like any other industrial project will create widespread contamination of air and water. Furthermore, many conservationists have highlighted the death of multiple significant habitats that deserve to live in their own right and are also necessary to help regulate planetary systems.

Governmental policy has turned to science to create thresholds for legally permissible amounts of contamination. This is called assimilative capacity, formally defined as the theory that “environments can handle a specific amount of contamination before harm is caused”. There is a final factor to consider, culturally we have come to accept that natural environments should be a resource for human use and exploitation. This perspective is rooted in supremacy narratives that put humans at the top of the “totem pole” rather than seeing more-than-human beings as Kin.

How governments arrive at air pollution policies and contamination allowances are dependent on science, governmental policies, and narratives that are culturally acceptable. It is also important to consider that currently policies and laws that protect polluters are all done without community consent. Therefore, in order for us to access air that is nourishing and clean, we have to employ an abolitionist strategy.

Another world is possible (an abolitionist strategy considerations)

Abolishing at its core is the official ending of an event, law, policy, or even state of mind. There is also a political element to the word, that has its roots in the Black and Indigenous Abolition movements which ended chattel slavery in what is illegitimately known as the Americas. The contemporary abolitionist movement refers to the dismantling of the ‘prison-industrial complex’ (PIC) - comprising “overlapping interests of government and industry that use surveillance, policing, and imprisonment as solutions to economic, social and political problems” (Critical Resistance, 2023). PIC abolition is centrally concerned with breaking cycles of violence, making legible where carcerality acts and is reproduced in proposed solutions to violence. Crucially, though, PIC abolition commits to being in perpetual practice of “rehears[ing] the social order coming into being” (Wilson Gilmore & Gilroy, 2020).

According to the World Health Organisation there are no safe levels of air pollution. Given this fact, we as citizens and scientists can no longer show a permissiveness or a tolerance to air pollution. Therefore, in the context of this project abolition means the end of “Right to Pollute Policies”. We would also like to introduce one more factor to the abolition conversation, which is the spiritual. For many of us on this project, we belong to Peoples and communities that have been historically marginalised by systems of supremacy that lead to experiencing air pollution at a disproportionate rate. Therefore many of us carry a deeply rooted and even Ancestral need to abolish what has harmed us for generations.

Many would think that science has to be politically neutral and therefore has no utility within a political space. However, science is a human cognitive output and like all other outputs it is intrinsically rooted in culture. For example, in western European culture, humans are put at the top of the cognition scale, therefore it has taken western science until quite recently to recognise that other beings such as trees and plants have complex intelligence. In contrast, many cultures of Turtle Island do not centre the human and long recognised not only the intelligence of more than human Kin, but also their wisdom and intelligence. We cannot separate science from culture. Additionally, science is a tool, one that allows us to systematically observe the world, so we can turn this into information for complex problem solving.

Therefore, for this project we are going to use abolition as our strategy to create a scientific design that contributes to the abolition work being conducted by communities all over the world. Abolition is a strategy that requires big mental shifts starting from knowledge roots, narratives, and moving towards cultural shifts that end with changes in the law. This requires time and certain considerations. Here we identify three, there are of course many more depending on your community and perceptions.

Further Reading

Meet the Team

Air is Kin is a project led by a wide range of practitioners from leading university research centres, primary healthcare trusts, and grassroots campaign groups.

Air is Kin

Air is Kin is a project led by a wide range of practitioners. Below are the team members.

Araceli Camargo

Araceli is a neuroscientist and health justice advocate working at Centric Lab. Araceli is a descendant of the original Peoples of Turtle Island.

Prof. Ilan Kelman

Ilan is a professor of disasters and health at University College London. His research interest is linking risk, resilience and global health, including the integration of climate change into disaster research and health research

Dr. Julia Pescarini

Julia is an assistant professor at London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine interested in understanding how poverty, vulnerability and deprived living conditions, included in the broad context of the social determinants of health, affect the chances of people becoming ill and how we can mitigate that.

David Smith

David is the South West London-based founder of Little Ninja, a movement which launches campaigns to reduce air pollution by targeting harmful traffic practices, such as idling, and evidencing the real impacts of campaigns such as Low Traffic Neighbourhoods have on marginalised and vulnerable communities.

Dr. Rhiannon Mihranian Osborne

Rhiannon is a junior doctor, researcher and organiser. Her work focuses on environmental justice, access to medicines, and re-imagining health beyond capitalism and colonialism.

Angela Fonso

Angela is the coordinator for the campaign group Clean Air for Southall and Hayes, a campaign group campaigning against the environmental injustice caused by a local housing development on an old gasworks site.

Dr. Joanna Dobbin

Joanna is a doctor based in Somers Town, Camden who is passionate about health as a human right and campaigning for accessible healthcare to all.

Stuart Bennett

Stu is campaign coordinator of the Save Rimrose Valley campaign, an environmental campaign which successfully saw to the cancellation of a destructive government-led road proposal Rimrose Valley Country Park in North Liverpool.

Daniel Akinola-Odusola

Daniel is a data strategist with a background in neuroscience. Daniel has been working at Centric Lab for over 6 years ad has been instrumental in the development of its data projects, studies, and approach.

Dr. Emily Parker

Emily is a resident doctor working in paediatrics in Newcastle who advocates for the role doctors can play in safeguarding children from the harmful effects of pollution.

Josh Artus

Josh works at Centric Lab with a focus on the built environment and policy.

This project is in partnership with Impact on Urban Health

Further Reading

Air is Kin Academy

This Academy is a self-directed learning tool built as a “Miro World”. Across a number of modules and lessons you are able to be part of a connected and educated community can help move your advocacy forward at a more gentle pace. This includes its history, the science behind air pollution, how air pollution affects our bodies and minds. We have also added lessons to nourish and inspire your journey.

We cannot do this work alone. Being part of a connected and educated community can help move your advocacy forward at a more gentle pace.

For a better viewing and interactive experience please click here to access the Miro board and begin your journey!

Further Reading

Drop in Sessions

These sessions are an opportunity to ask questions about the programme, ask for advice if you are facing a pollution event, or ask questions about a specific challenge you are facing.

Air is Kin

As part of resourcing clean air advocacy movements and campaigns, we are offering free virtual drop-in sessions.

These sessions are an opportunity to ask questions about the programme, ask for advice if you are facing a pollution event, or ask questions about a specific challenge you are facing.

They will be held between 7-8pm UK time and will be held as safe spaces for all.

To join please enter your name and email address below for the dates you want to attend and Daniel will be in touch with a link to join.

Tuesday 26th November 2024

Tuesday 11th March 2025

Tuesday 10th June 2025

Tuesday 9th September 2025

Further Reading

About the Project

This is a live, working summary document of the Air is Kin Project. We are prototyping a method for working not only with communities, but also with the wider public. Science is often done behind closed doors and with little to no public knowledge or input. Whilst it is not realistic to include every single member of the public, we hope that through this document, we can keep a clear line of communication with the general public.

Air is Kin

This is a live, working document. Meaning, that throughout the course of this project we will be updating it. You can read it in full by scrolling over the embedded document.

If you have any questions about what is written here please contact us via email: aik at thecentriclab dot com