A Community Leaders Health Impact Assessment Workbook

This light-touch approach is designed to support community leaders work with speed to capture key insights about community health and the impacts that a policy, plan, or project may have.

This workbook is a light-touch assessment document whereby community leaders help define the criteria and methods through which their people’s health is impacted by a potential plan, policy, or project.

-

This guide is for people who work in-between authorities and communities. It is for people who are able to convene community leaders based on existing relationships and work together in their best interests. It is for people who are able to take the outcomes of this guide and take it upstream to people who need to see it urgently.

-

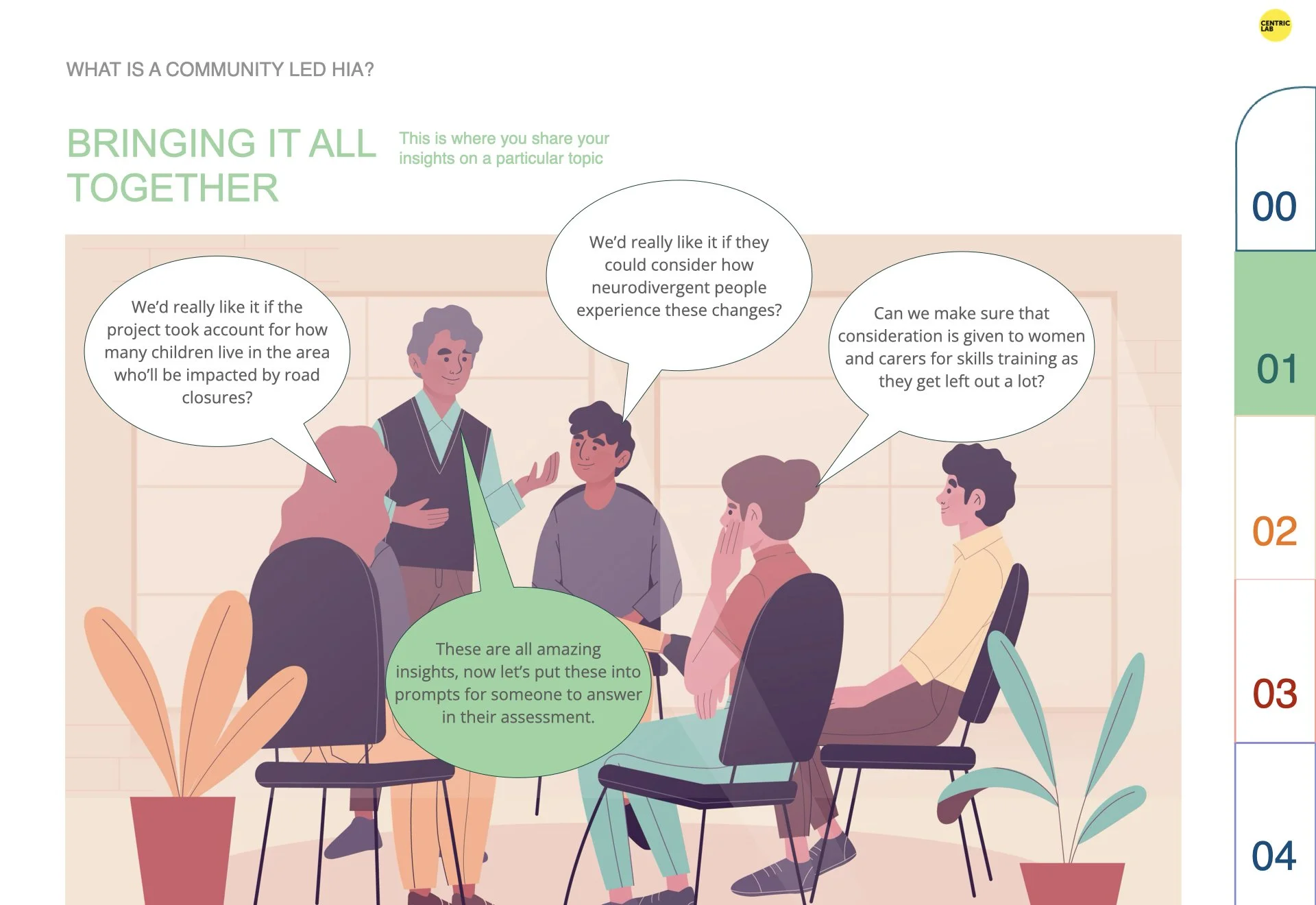

A community leaders HIA is a rapid-fire approach to harnessing the knowledge held within communities around how systemic injustices create health outcomes. It provides a practical approach to ensuring that a justice led systems based approach to judge the potential health effects of a policy, strategy, plan, programme or project on a population, particularly on vulnerable or disadvantaged groups are considered.

-

When a large policy, project, or change is due to occur in an area and decision makers need to ensure they minimise the conditions that impact health.

NOTE: This guide is intended as the first of two steps. For the real impact of this work we advise the use of the CHIA toolkit, which is a process that involves members of the public and wider stakeholders.

-

This guide is designed to support organisers and staff to facilitate one or two workshops. Facilitators should read the guide - and any additional reading - and prepare to host a session with community leaders. These leaders should be people who hold trusted leadership from the community they represent who have consent to communicate key insights on their behalf. By gathering these leaders together it’s possible to produce a rapid-fire health impact assessment that is based on the lived experiences of people most affected by the status quo.

This roots of this workbook are in our collaboration with Clean Air for Southall & Hayes. Since 2018 we have been working alongside the grassroots group in their efforts for health justice. This workbook is the result of a project we explored together when towards the end one person said “we should share this process with others like us, everyone should have this opportunity to advocate for their health in this way.” Please consider supporting all grassroots groups near you. They are the lifeblood of change.

You can read a peer-reviewed journal article on our journey and methodology here.

To access the workbook please fill in the form below

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU

If you download the workbook we’d love to hear from you about your experiences. We can also offer advice and support.

p.s. to save the pdf to your computer choose a print as pdf or save as option from your computer.

Further Reading

It’s not the what, it’s the how

When Southall residents starting falling ill due to what they suspected was carcinogenic chemicals in the air from a local factory redevelopment, local authorities reassured them any contamination was within safe levels. The Centric Lab team tell the story of their partnership with the community to reimagine the Health Impact Assessments used to define safe levels and ensure it reflected the lived experience of the local community.

INTRODUCTION

This essay was commissioned and first published by the British Science Association in February 2025. It covers the story of Centric Lab and Clean Air for Southall & Hayes collaborating to rethink the health impact assessment.

“People who reside in, and have history with, neighbourhoods know them best. They are best placed to identify what happens when policies intersect, because they live the outcomes of these relationships. This knowledge needs to be respected in the same way as professionals with acronyms at the end of their names, who despite having knowledge in the intricate application of policy work within a system, don’t experience the outcomes.”

“One night, I opened my front door to such a strong gas smell I actually thought someone was trying to gas me and I rang the police”.

These are the words of Janet Griffiths from Southall, west London. Janet is part of a grassroots campaign group called Clean Air for Southall & Hayes (CASH) and this research project has been based around the experiences of this group working in collaboration with Centric Lab, an independent science lab. Good community research should always centre the story of the community it is serving. This story is about people experiencing a health injustice through the systems that govern them. Like many stories of injustice, this one seeks a just ending - an outcome rooted in dignity and a healthy existence.

Good community research should always centre the story of the community it is serving. This story is about people experiencing a health injustice through the systems that govern them. Like many stories of injustice, this one seeks a just ending - an outcome rooted in dignity and a healthy existence.

Residents from Southall protesting in 2018 about the gasworks site with contaminated land

SUMMARY

Centric Lab and CASH began working together in 2018, finding each other through social media. Since then, we have aimed to co-produce justice-led research on the impacts of air pollution on marginalised communities. This essay tells the story of rewriting the rules of a Health Impact Assessment, a co-production journey that has not only helped a community identify and evidence racial health inequalities but also raised the profile of the issue and led to similar projects across the UK, whilst also demonstrating opportunities to improve policy design and implementation. And although the ending has not yet been written, the impact of the work is being felt more widely than just the story of Southall.

The community-led approach that we advocate for:

Allows for people’s lived experiences to shape the systems that change their neighbourhoods and livelihoods;

Creates dialogue as opposed to relying on a system of scoring, moves towards a less data determinist, more accurate and nuanced identification of health impacts;

Influences what democracy, equity, ethical use of data, and sustainable development look like

Co-production with justice-led research and practice can be a site of healing, repairing harms caused and creating new systems of governance and care. This project explores that journey.

BACKGROUND

In 2017, soil remediation works began on a highly contested redevelopment of a former gasworks and chemicals factory site in West Southall. Local planning authorities and residents had raised concerns about developing the land, however the Mayor of London’s Office believed that as long as regulations were met this site would “provide thousands of the homes and jobs Londoners need” and thus consent was granted, beginning a 25-year regeneration project.

Soon after, a putrid gasoline-like smell filled the air, giving residents cause to believe that carcinogenic chemicals like benzene were no longer in the soil, but airborne. Illnesses started to amass. Residents started to complain of headaches, sore throats, chest pains, being short of breath, dizziness, fatigue and more. Others resorted to hiring oxygen tents for their children to sleep in .

This went on for many months and residents began to organise, forming the campaign group, Clean Air for Southall & Hayes (CASH). Despite continued protest and efforts to bring the situation to the attention of authorities for action, it seemed that nothing could be done - CASH were repeatedly assured that the levels of contamination fell within acceptable limits and all policies and regulations had been met.

To a community who had faced a long history of racial prejudice and been subject to past discrimination from those in power, this felt unjust, further exacerbating the systemic inequalities they had been subject to for so long

“No one wants to take responsibility for us and we’re paying the price with our lives. We’ve been knocking on the doors of the council, PHE [Public Health England], EA [Environmental Agency] and politicians for years,” CASH member Joginder Singh Bhangu told The Guardian. “Our community has fallen through the cracks.”

WHAT WENT WRONG?

In the UK, every new major property development, or policy change, undergoes a process in the planning stage to systematically identify and assess health and wellbeing impacts – this is known as a Health Impact Assessment (HIA) and refers to things like ‘safe levels’ of exposure to possible contaminants.

You may be asking yourself - how could it be safe if it's this bad for people?

Because of the theory around “safe levels” and policies not addressing the issue of community susceptibility.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) states that air pollution guidelines should be set according to the susceptibility of the local community. In social epidemiology, being more susceptible means some members of the public, located in certain geographical areas, are likely to have lower physiological thresholds to the pollution entering their bodies and more likely to experience negative health impacts.

When we came across the Southall development’s HIA, we realised that the process failed to reflect a scientific framework to contextualise the specific environmental, cultural, historic and social dynamics experienced by the community of Southall. Southall is an area of west London that experiences high levels of structural deprivation (as measured by the ONS Index of Multiple Deprivation) as well as pollution coming from a wide range of sources, such as asphalt plants, industrial business parks, and being downwind of Heathrow Airport.

Southall is also a predominantly multi-ethnic working-class and highly racialised community living in a structurally deprived environment where 41.4% of children live in poverty, higher than the UK average of 30%. Studies show Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic groups inhabit more deprived and environmentally polluted neighbourhoods.

Centric Lab neuroscientist, Araceli Camargo, summarised this by saying: “The specific challenges to the health of people in Southall, such as overcrowding, stress and poverty, should have been evaluated before introducing a major new source of air pollution.”

We asked ourselves: What if the template from which this assessment was performed was different? What if it reflected community life more? What would it look like if a community designed it? Could all these problems have been avoided?

As a team we agreed on the scientific and practical premise of what we were going to do: redesign an HIA template that reflected the lived experience of the community, backed by World Health Organisation principles and (neuro)scientific research.

THE SCIENCE

The innovative approach we took to the project was to base it in a scientific area of allostatic load theory. Allostatic load is the "wear and tear" on the body that results from the body's physiological systems working to adapt to internal and external stressors - the physical and mental health impact of chronic stress and life events.

This theory has a long history in justice movements, starting with the “weathering effect”, which highlighted the health disparities between African American men and women. It supported justice for African American women, as due to their biological stress burden they suffered more acute symptoms of depression, dementia, and neuroendocrinological diseases.

The greater the existing number of stressors (psychological or environmental), the greater the risk of being more susceptible to impacts on immune systems. This area of work, rooted in the study of the HPA-Axis16 - a full brain-and-body communication system that create a feedback loop of hormones to enact and regulate your body’s stress reaction. This area of science helps build a physiological bridge between the urban environment and the human body.

This means that collectively we can no longer frame health through individual activities and behaviours but need to understand health from an ecological point of view. This allows for the quantification of activities, pollution, services, and resources that take place in an area and using this as a science informed proxy to qualify the levels of stress put upon people by the socio-political, and economic, conditions they live in.

WHAT WE DID, AND HOW

Co-creating research in direct solidarity with communities has the capacity to be healing for people who have felt abused by powerful systems. The solidarity aspect is especially important, as it means that scientists, authorities, and organisations wait to be invited and meet the communities where they are emotionally and practically. It also means “walking” at the community’s pace and moving out of the way so they can continue to identify the journey to justice .

To actively work on something that can change future practices, as well as support others in the same advocacy space, is meaningful. But, at the same time, this can be retraumatising, especially for those who continue to live in the moment. Every meeting attended; response to consultation; networking activity, can re-harm. This meant that, with Centric Lab as facilitators, it was necessary to design care and dignity into our process. The project’s respective leads, Josh Artus (Centric Lab) and Angela Fonso (CASH), met in advance and identified an approach that would be gentle on the wider CASH community, building on the long-standing research relationship that was set up in 2018.

We wanted to redesign the whole system, not just rewrite the existing document template. A key first step for this was just to create space for every issue, thought and experience about what had happened to date to come out and for it not to be contrived into a particular policy or consultation agenda. It was fundamental to the success of the project to create a space for everyone who would be working together to be heard, and to listen, free from any policing - something that doesn’t reflect from many people’s experiences in typical institutional or corporate settings.

As time went on, we began to see how the experiences we shared mapped on to the WHO four interlinking values of democracy, equity, sustainable development and the ethical use of evidence. Had the process started directing where feedback would be given, we would have been creating a hierarchy, a power imbalance, and removing the humanity of the people involved.

Also critical to the success of this work was giving it time. Over the following months we met fortnightly in the evenings to collectively work. We all agreed a schedule of work – exploring what HIAs had been done, what we thought of them and what an alternative approach might look like. We began to identify underpinning principles - we asked ourselves, ‘What does good health look like?’ and ‘How do we see that in our neighbourhood?’. We developed a shared theory of change, and reflected as a research team on how this piece of work would shape the ongoing goals of CASH.

We then started to write our assessment template. We went through our notes and pulled out items that were key health indicators, and then set metrics to measure them by, and link to existing data sources. This meant that someone else could use this template without us. It was crucial that we used existing datasets as a way to validate the professionalism of the work.

When we got to the end of our first phase, we arranged an online group session with a number of other grassroots organisations in the UK who were in a similar situation. This helped us sense-check progress and sow the seeds for future relationships with those who might want to work with us should we receive further funding.

Finally, our community-led Health Impact Assessment (CHIA) template was ready. To support others in this we turned our journey into an open-source exercise book which we shared freely with our networks. We went on to meet with the leader of Ealing Council and members of the London Assembly and Green Party, as well as other organisations who wanted to listen and engage. This was great, but we felt it was more important to share the process and the work so that others could organise and benefit in the same way.

With further support from UKRI’s Community Knowledge Fund and charity Impact on Urban Health, we were able to facilitate a learning programme for 10 groups from around the UK. The programme started in early 2024 with the intention of groups developing their own CHIA throughout summer and autumn. A key win for one group in particular has been using their CHIA to demonstrate to their local planning authority that health inequities for the local racialised communities were not being taken into account in the Local Plan, and policy amendments are now being made.

WHAT DID WE UNCOVER?

Here we come back to our opening statement: it’s not the what it’s the how.

We discovered that in general, we agreed with a number of the health indicators used in the various health impact assessments. However, we disagreed with the approach to how the data/metrics and evidence were being applied.

In particular, we debated whether new housing alone is a positive indicator of improving local health, given the experiences of unaffordability, toxicity of new construction and design materials, and insecurity of tenure. We challenged the notion that the mere provision of a food retail unit owned by a multinational could be considered a positive indicator when it does not take into account the cultural needs of local people. Lastly, and most importantly, we questioned whether the HIA process itself embodies good governance and democracy; we felt that it was a process being performed, delivered, and regulated behind closed doors without any input from the very people it will impact.

CONCLUSION

Understanding how a system behaves is crucial to changing what it does.

People who reside in, and have history with, neighbourhoods know them best. They are best placed to identify what happens when policies intersect, because they live the outcomes of these relationships. This knowledge needs to be respected in the same way as professionals with acronyms at the end of their names, who despite having knowledge in the intricate application of policy work within a system, don’t experience the outcomes.

CASH and Centric Lab have worked together to reimagine Health Impact Assessments, giving power to citizens to shape how health in an urban context is experienced. A CHIA is a method to “build policy that protects community” - Angela Fonso, CASH. The CHIA toolkit and example we created and published is downloaded weekly. Community groups and like-minded organisations across the UK, Ireland, and the USA access the works to continue their advocacy.

As more blocks of high-value apartments are permitted on the gasworks site today, CASH continues to advocate for greater community voices in planning and local area management. If only a CHIA like ours had been in place at the beginning, we may not have had to do this.

CASH's story may not have the just ending it deserves, but it will hopefully influence others' stories so that people can get on with their lives and not have to protest for something as fundamental as their health.

Further Reading

Systemic Thinking

This Learning and Reflection piece looks at how systems thinking in context to the Determinants of Health can expand indicators and metrics on health so that they become more justice and lived experience led.

The planning documentation seeking consent to redevelop the Gasworks in 2008 appears to have been influenced by the 2003 UK Government paper ‘Tackling health inequalities - a programme for action’. Whilst the 2003 report uses meritable actions for reducing health inequalities they fail to address the systemic conditions in which the recommendations sit as well as their abilities to unintentionally exacerbate determinants of health if not they’re not addressed at source.

Increasing opportunities for employment has typically been seen as pathways to reducing health inequalities as it relates to the ability to purchase good quality foods, access to services, and the chances to access a quality of home that would infer better health opportunities. However, as many have pointed out, if the economic system in which the employment opportunities sit are from extractive methods this can have an impact on a range of systemic factors that influence long term health.

If labour rights are diminished in the name of powering the economy this can result in unfair working conditions such as zero-hour contracts, shift-work, and a hostile and fragile employment status, all of which impact health in a number of ways.

Additionally within the extractive economics framing is the capacity for business and economic practices to impact wider determinants of health such as climate change and political instability. Another example of an extractive economic practice can be whether systems contribute to community wealth building or not. Katz et al from the Drexel University Lindy Institute for Urban Innovation have demonstrated at length in Towards a New System of Community Wealth how without addressing community wealth building from the ground up, a slow erosion of social infrastructure and capital takes place where local tax bases diminish whilst conditions for quality of life also decrease.

This is one example of good intentions not accurately reflecting the conditions in which they sit. Another example can be housing, and to keep it simple, whilst ‘Tackling health inequalities - a programme for action’ may state that “good” housing is a pathway to good health there are issues to navigate such as the number of volatile organic compounds found in modern building tools, the quality and quantity of tenure for those that rent is crucial, and whether the types of homes being made reflect the cultural realities of modern life - such as multi-generational households. Without these issues being addressed more accurately the promise of a direction of good health can in fact lead to a different set of health problems.

This brings to light the need for the inclusion of a Determinants of Health framework to guide the conditions under which indicators and metrics within an assessment sit. Sir Michael Marmot has worked to establish the Social Determinants of Health in modern British lexicon however it’s time we go one-step further and ensure that commercial and political determinants are also considered - side note: we take issue with the term “social” as this implies there is an inherent societal, or personal, attribute that causes factors such as unemployment (e.g. lazy) and treating them as issues at a local level, whereas we would refer to them as “socialised” determinants of health as they are the conditions set by political and commercial actions, such as the investment in employment opportunities and training by governmental and industry actors.

Lastly, it’s worth bringing to light the timescales involved in such projects. A document from 2008 refers to another document in 2003 (itself most likely produced over 2001-02) and influenced an activity taking place in 2018. It can be argued that in 2003 (white) society was less aware of social determinants of health and systems thinking theory and practice and therefore it wasn’t debated as extensively. However, by the mid-2010s the breadth of knowledge and insight produced in these fields is undeniable. By these points in time, and certainly in response to the 2008-era Global Financial Crisis, the social awareness and practice of systems design were mainstream. Meaning that we have a time-based problem.

Conclusion

We ask a simple question that surely planning processes should have mechanisms in place to be reflected in a more real time, socially relevant manner? Why couldn’t a process such as an HIA be completed with up-to-date theory and practice be submitted within 12 months of an application?

Further Reading

Top-Down vs Bottom-Up Indicators on What Makes a Healthy Place

This Learning and Reflection piece looks at what happens when a bottom-up approach is taken to asking the question of what makes a healthy place?

In the paper The Messy Challenge of Environmental Justice in the UK: Evolution, Status and Prospects (2019) Gordon Mitchell discusses the differences of environmental justice perspectives, approaches, and practices between the USA and UK/Europe. They argue that in the USA environmental justice has primarily been led and culturally shaped by grassroots community groups. This has resulted in the narratives of environmental justice being a socio-political issue given the acute geographic localisation of injustices. Whereas in Europe the narrative has been shaped by NGO action from the 1970s on the problems of carbon emissions being the problem of climate change, framing it more closely to a broader socio-economic issue. A bottom-up versus top-down approach.

So what about Health?

The Health and Care Act (2022), and its predecessor the Health and Social Care Act (2012), do not provide an active working definition of health. It is often assumed in these cases that any understanding of health is through the WHOs definition: Health is a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity. The Ministry for Housing, Communities, and Local Government also does not offer a working definition of health in its overarching guidance document the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF).

A lack of working definitions leads to interpretations, and as people such as Alastair Parvin write, British planning law is a culture of interpretations rather than rules, showing this is by design. Based on people's own attitudes, learnings, and epistemological framings they can make interpretations in many different ways.

This means that Local Plan policies can be designed using “legitimate evidence” and be problematic as depending on the subjective framing of authors and publishers the work can be biassed, misinformed, ignorant, or at worse, malicious. Therefore, well-meaning references to health around initiatives of access to natural space, good housing, local services, etc. the policy interpretation can exacerbate existing inequities when they fail to address the social, cultural, and political/governance issues that underpin them.

What did our research show?

In the case of our HIA we noticed that when reviewing the document September 2023 Rapid Health Impact Assessment for The Green Quarter by planning consultancy Lichfields, which used the GLA advised HUDU template, that a generalised access to food spaces would be seen as a positive health indicator. However, what makes food a healthy benefit for local people can mean many different things. For example, the Green Quarter HIA refers to the diverse demographics of Southall but the guidance for determining the health impacts of food spaces through new real estate don’t reflect this. Meaning that the provision of another large scale supermarket may tick a box and present a positive benefit to the needs of the community on paper but not meet the nutritional needs of all cultures, resulting in the need to travel further to access goods or go without, unhealthy in many ways.

When comparing the indicators from the HUDU template to ours we saw many comparisons. However the metrics were different. Our more bottom-up approach also brought in a wider range of issues that demonstrated what helps sustain a healthy place from a community point of view. For example, in our HIA we created an indicator asking for the assessing in the numbers of school aged children in and around a construction site. This was done under experiencing the impact of construction noise at critical times family-oriented times, such as when children are at home trying to do homework or for dinner time. Disturbances to this can cause multiple systemic issues to family life and increase stress on everyone involved. The indicator asked to a use of ONS or local authority data to understand the potential scale of impact, and therefore augment actions to reduce impacts. The solutions on which could be a range of things depending on the situation, for example, this could mean traffic management at specific times; noisy construction avoided between hours such as 3-6pm; a special after-school homework place for children and families otherwise impacted by the noise.

Another indicator/metric difference was on social infrastructure. The mere mention of providing social infrastructure in a planning document receives a positive mark however that can mean many different things. In the case of our HIA we talked about this meaning more secular social spaces, and a focus on childcare provision given the challenges many families and communities are facing over costs and lack of services. Inadequate provisions for childcare can reduce people’s capacity for employment in full- or part-time work or even shift-work, meaning the aforementioned positive benefit of employment as a health indicator being meaningless to some. Inadequate provisions for childcare can also mean children spend less time with their families or are forced to live irregular patterns, which goes against the majority of research and guidance that children need stability and routine in early years to develop good mental health. Disturbances and insecurity at young ages can lead to developing emotional, and thus behavioural, problems impacting school and social lives. The rest speaks for itself.

Conclusion

Whilst we mostly may be on the same page around issues, the approaches, framings, and details are different. This is what gets lost on a technocratic approach that becomes revealed when doing things bottom-up. The main issues remain however the methods evolve.

Further Reading

Democracy in Name or Process?

This Learning and Reflection piece on the CHIA process discusses the role of governance and democracy. It contextualises the WHOs agenda of "democracy" through a lens of governance and distributed power in reference to the people of Southall's experience.

CASH member Joe Banghu has frequently challenged members of Southall’s political institutions on their capacities to uphold and represent the voices of the people they represent. Many like Joe have grown to feel that those who propose, draft, write, and approve local government policy have too much power, can be easily swayed, and whose only oversight is an election cycle.

Once the ballot box is closed, so does accountability. This has very much been the case of a community advocating for the people who politically represent them to stand alongside and fight for them. It became apparent to us during a call with Ealing Council’s leader, Peter Mason, on this project that despite being acutely aware of the problems the community was facing, planning and property law meant that it is very hard and legally (and politically) risky stop the development taking place unless it was demonstrably in real time breaking the laws under which its consents were granted - Britain is arguably built on the epistemological basis of property ownership is everything.

When reviewing the initial 2008 planning documents for the Southall Waterside development it was clear that all parties were aware of the problems of contaminated land. Even to the extent of drafting the following language in West Southall Environmental Statement, Volume 1, Part D:

“Excavation activities during construction or once the Site is occupied may disturb contaminants currently immobilised within the soil profile to create new, or extend existing, pathways. This would introduce additional contaminant sources with new or faster pathways to identified receptors. Potential health effects could occur including ingestion of toxic heavy metals and skin irritation caused by contact with hydrocarbons. These human health pathways and effects are most likely to concern on-site workers, with limited exposure to off-site receptors...

“…Remediation works will need to be managed in accordance with best practice and controls [sic] measures used during these works so as to reduce the likely significant effects as identified above. If no measures are introduced, the existence of contaminated land at the Site is identified as potentially causing moderate adverse effects to local receptors (local controlled waters, construction workers and local residential areas)” .

Frequently during construction members of CASH were aghast to see the tarpaulins of soil hospitals flying around in the wind. This was not a case of illegal activity but of poor compliance and oversight - who is there to hold people accountable to the nuances of planning applications and conditions of approval? Reporting mechanisms between citizen-to-authority-to-accused are laborious and often a battle. Anyone who has tried to report neighbourly issues to authorities have often given up or found themselves acting as pseudo-detectives building a case against another person, not something we should need to do to uphold a sense of dignified living.

Therefore, when we think about the term ‘democracy’ in light of the WHOs guidance we chose to expand what this could mean from a systems perspective. For us, democracy in this case was seen more in terms of governance. What systems are in place to ensure that a community-led voice has the ability to feedback on the successes of compliance? This meant that for us that the ecosystem in which the HIA is performed is as crucial as the assessment itself. We chose to rewrite the rules and ignore current political hierarchies and imagine what would make a successful HIA in a community's eye.

There were some key issues to resolve: who owns the data; who owns the process; who oversees the process; who validates the outcome? For us this meant redesigning the system:

The community owns the HIA and is requested by the applicant.

A member of the community is nominated to oversee the process.

Results are fed back to the community in a discursive format in order to co-design solutions.

A member of the community is nominated to oversee the compliance of the HIA related planning conditions.

The completed HIA is returned to the community and made available to all other community organisations across the UK.

This challenges the status quo in how an HIA is performed, often done by individuals with no relationship to the local community or area and at times without technical or professional insight/qualifications on health, and the results are rarely shared with members of the public and stored within inaccessible (to the lay-person) planning websites.

Again, it is not the form that is wrong but the method/function, the cart leading the horse. Upholding democracy is predicated on robust governance systems and transparency.

Joe Bhangu of Clean Air for Southall & Hayes

Further Reading

The Making of a Community Health Impact Assessment (and Toolkit)

This piece documents the process that was taken in how we created our Community Health Impact Assessment. We've done this to show what journey we took in the aims of transparency and hopefully inspiration to others.

There is no defined HIA template, only guidance; the London NHS HUDU template greatly differs from the Public Health Wales HIA on the health impacts of climate change . This means that it is malleable as opposed to other technical guidance - perhaps an ironic benefit of there being no definition of health in the context of urban planning (via the National Planning Policy Framework).

Getting Started

We wanted to let our imaginations and lived experiences determine what would make a successful HIA. We then would use what we have created and hold it up against what is produced to see any alignments or discrepancies.

To guide our collaboration we reviewed a number of articles and studies on co-design, such as this piece and this, as well as looking at service design models - given the output of this work questioned how a system operates with the various stakeholders.

The project was made possible by a small grant from the Community Knowledge Fund to run a pilot project with capacity for a stage 2 funding opportunity to grow the work. Therefore we designed a programme of work that was relevant to the resources (time/money) we had available. Below is the programme.

The Value of Scheduling and Creating Boundaries

The project leads from CL & CASH agreed on a schedule of work and presented it to wider members of our respective organisations in an evening virtual call. We then agreed on a calendar of activities that were inclusive of people’s needs and boundaries.

We also agreed that there would be some shared responsibilities in the group but they would match each other's respective capabilities as to not overburden people - this was after all something being done in evenings and spare time . It must be noted that everyone received remuneration for their time equivalent to that of a professional. We are all experts of our lived experiences, people shouldn’t need acronyms at the end names to be paid for their expertise.

Within the programme schedule we designed a number of exercises that would guide our thinking in what would make a successful HIA.

Over the course of 4 months we met through fortnightly virtual calls in the evenings. For the most part we met as a group but there were daytime sessions for certain members to research specific issues that didn’t merit inclusion of all people’s time.

Starting the Work

Our approach to ensuring this was justice and lived-experience led was to centre conversations by looking at the problem holistically. We did this by starting the first session on sharing all the blockers the members of CASH had experienced in advocating for their health, including engaging with health systems and all related departments.

We felt that this would shed light on how the HIA could work in a multi-stakeholder and cross departmental framing rather than just looking at improving the margins of the current status quo within planning policy.

The following is an outline of the work sessions that followed, in order:

Reviewing what an HIA is via the current literature, guidance documents, and language to see how it works and reflects recent experiences.

Reviewing the number of HIAs performed for planning applications to the local planning authority, and regrouping for sharing findings.

Coworking to discuss what the HIA process and system misses about health in community oriented life.

Developing a series of principles to guide how our HIA would be developed and performed

Developing a theory of change model for how our HIA would work to have success.

Lastly explored whether the HIA should interlink to other planning conditions such as obligations from S106 Agreements and Community Infrastructure Levy however we opted to not go further with this work as it would open up additional bureaucratic and political layers that would likely impair the success of community-led action.

Through all sessions we allowed for questions to be answered in an open manner. For example, when asking what “good” looked like there was no parameter on whether this was explicitly about the process or outcome. This ensured that a full range of ideas were brought forward and discussed.

Results

For this section we’re going cover what we discovered and learnt through the research phase.

The members of CASH experienced various levels of gaslighting, being told that it was “only them” experiencing these issues, “no-one” else is complaining, and “it’s more likely a result of other factors in their lives”. Their requests for help and claims of injustice were brushed away as authorities could not point to other data sources, such as GPs, to verify that this was a public health issue. However, using a very metric of GP visits be local residents complaining directly of air pollution related problems is problematic, Southall is a predominantly working class area with many parents working shift-work meaning accessing GPs can be difficult; childcare can be complex if taking a child out of school for a GP appointment; there are internalised stigmas in taking children out of school or taking sick days from work in order to keep up appearances in a racially prejudiced society. This institutionally led to an erasure of their lived experiences and a prejudicing of their lifestyles.

Over time the members of CASH experienced what can be described as being “cancelled” - they were excluded from a variety of public engagement activities despite them being an active organisation concerned with health and placemaking matters. According to the Oxford Dictionary, being cancelled is ‘ a systemic approach to removing someones agency to express their views that challenge an orthodoxy’. This can be seen in their exclusion from public engagement events due to their challenging of the local authority and developer’s agenda. Therefore, community consultation continues to be seen as a one-directional process parading as equity.

When given a platform to discuss and present their informed criticism of the real estate housing development it felt that this was just deference politics at play, that they were being placated through a thin veil of ‘democracy’ through participation when in reality the concerns they were raising could not be actively acted upon by the authorities who would need to act on their behalf, meaning little was done from the feedback.

Academic institutions offered support but the length of work, perceived extractive nature of research, and lack of control over research methods presented another frustrating avenue in aiming to demonstrate their injustices through “legitimate” evidence. Grassroots organisations around the world are forever told to present legitimate evidence and hard data beyond their own views. This is knowledge supremacy and a suppression tactic. Knowledge supremacy is a knowledge pool that self-identifies as supreme to systematically dictate the knowledges that are valuable, trusted, and acknowledged, resulting in hegemonic policies that affect our health.. Legitimate evidence often means something that is produced by “professional” researchers or academics. Therefore, the only accepted avenues to demonstrating ones cause for concern are met with impractical realities resulting in grassroots groups and citizens impotent in fighting their case on equal, or even equitable, terms.

Poor governance was rife, there was a perception that local government figures, such as councillors, were easily manipulated through investments in initiatives they were keen on and increases in their own levels of power, such as being invited to sit on new committees and representative boards in the borough. A major frustration was the lack of public oversight in how this unfolded over time and that this was a perceived infiltration of local systems by foreign actors with vested interests.

Early planning documentation demonstrates a distinct awareness of the problems related to contaminated land and the need for high levels of due diligence and compliance in remediation techniques if works were to take place - contrary to personal stories on the quality control of soil hospitals where tarpaulins would be seen flailing in the air at times.

Language in current literature is opaque and to be justice-led need stronger definitions - e.g. social determinants of health only looks at downstream outcomes rather than upstream causes and actions. The NPPF offers no definition of health in context to the built environment other than some macro objectives of safety, natural environments, food options, etc., however this ignores the biological relationship to the built environment as well as how cultural differences influence matters. This means that “health” is open to interpretation by local planning policy officers resulting in unintended consequences of exclusionary practices or at worse discriminatory practices due to a person’s personal views on what makes a person healthy.

In the cold light of day there appears to be low-to-no accountability on what is produced via an HIA. Without different indicators, metrics, and outcomes measurements the results of an HIA are not ‘material considerations’ and therefore have no legislative or policy powers to ensure accountability.

There is an apparent lack of connection of HIA to other authority departmental policy initiatives. It was hard to identify how a HIA through the planning system related to initiatives from other departments such as social care. CASH felt that given the power that local health boards, like Primary Care Trusts and Integrated Care Boads, have they should be a stakeholder in the process - whether that be developing HIAs, being connected to the activity, reviewing applications alongside stakeholders, or being connected to and holding to account the outcomes.

Accessing information about HIAs at the local planning authority levels was very difficult. Local planning authority websites do not allow for the easy identification of this information. This demonstrates a lack of democratic transparency.

Conclusion

Having reviewed documentation there is an overwhelming feeling that assessments such as the HUDU template are self-serving and designed to support policy rather than people. In the document September 2023 Rapid Health Impact Assessment for The Green Quarter by planning consultancy Lichfields a project that has repeatedly caused harm to local community members has scored overwhelmingly positive. Make of that what you will.

We however see this as a form of corruption; a system designed to advantage one party through “organised” means. Rather than a scoring system it was beleved that any indicator and metric should be looked at independently and used as a discussion point within planning with relevant stakeholders (namely, local residents) for a solution co-design process - and not a box-ticking one that currently exists.

“We are all experts of our lived experiences, people shouldn’t need acronyms at the end names to be paid for their expertise.”

Further Reading

The CHIA Learning Programme 1

This piece documents the process that was taken in how we created our Community Health Impact Assessment. We've done this to show what journey we took in the aims of transparency and hopefully inspiration to others.

This is a peer-to-peer co-learning programme for urban(isation) focused community groups to develop community-led Health Impact Assessments. This is a programme for people and organisations who want to address the ecological systemic factors that influence our health at the local policy level, and seek lasting change to the places where they live.

-

Institutionalised framings attribute the worsening health of the population to our individual behaviours and lifestyles. This approach ignores the harmful impact of the many environmental and psychological stressors we’re exposed to. Such stressors include air pollution, job insecurity, and poor social infrastructure; all of which put stress on our biological systems and render us more susceptible to immune, metabolic and hormonal issues.

Given the importance of our environment on our health, you’d expect that the billions of pounds being spent on urban regeneration would have a positive impact on health outcomes. However, this is not the case.

Our experiences and research highlight that the methods for assessing the health and well-being benefits of urban transformations are flawed and require a fundamental overhaul. Further, this should be led by the communities that the policies impact.

-

Amongst the messy planning policy system is what’s called a Health Impact Assessment (HIA). It’s advised by the World Health Organisation (WHO) as a practical approach used to judge the potential health effects of a policy, programme or project on a population, particularly on vulnerable or disadvantaged groups. This concept is integral to the UK planning system, to the extent that the NHS London Health Urban Development Unit recommends the integration of a 'community-led HIA' into a Neighborhood Plan.

We have identified that targeting this piece of policy practice is a key opportunity to radically change the conversations and dynamics in which health is impacted. It is based on asking a simple question: is a project or policy increasing or decreasing a community’s exposure to environmental and psychosocial stressors as a result of their interventions?

The practical opportunity is to design a culturally and community appropriate baselining health assessment. This would then be used to navigate conversations between authorities, changemakers (typically real estate developers) and communities focused on mitigating and addressing the various determinants of health often overlooked in the current planning process.

Central and regional government guidance directs the importance and role of community engagement in the planning system. Instead of waiting to be asked to engage, take the solution to the table and show how things should be done.

Learning Outcome 1

We will be learning the link between Health Impact Assessment and environmental/health justice.

Learning Outcome 2

We will be learning how to use Health Impact Assessments as a tool for community led planning, so neighbourhoods begin to reflect community imaginations/visions.

Learning Outcome 3

We will be learning how to link HIA to improving community health

FAQ’s

-

This is a peer-to-peer learning and doing programme focused on supporting place-based community organisations exploring and delivering a community-led Health Impact Assessment fit for their area.

This programme supports those that want to embed the intended WHO values which are as follows:

Democracy (promoting stakeholder participation);

Equity (considering the impact on the whole population);

Sustainable development;

The ethical use of evidence.

-

From NGO to local government policy guidance a Health Impact Assessment is recommended to safeguard the health and wellbeing of people, identify risks as well as positive impacts available when a new policy or change is being considered. Principally, a Health Impact Assessment is something performed by an organisation evaluating the impacts of their changes. This could be a policy, such as a transition to net-zero, or a physical change, such as the redevelopment of a large urban brownfield site. The factors in the HIA are considered and debated in context to whether something is approved or not, or at least how to manage the process. However, the current methods in how this is performed does not uphold the guided values from the World Health Organisation, principally the level of democratic stakeholder participation. Therefore, by designing what this assessment looks like in practice it is a way to have more impactful, transparent, and democratic conversations with stakeholders.

-

This programme is an opportunity to engage with peers, be inspired by domain experts, and be funded to deliver a community-led HIA. This programme is for those who feel that the correct practices are not in place and have a vision for making a lasting difference in their local area - a neighbourhood, district or even local authority region. Over the programme you will be inspired by guest speakers on a range of topics, co-learn from your peers, and work towards creating a layer of practice that has the potential to seamlessly fit into existing policy guidance.

Each participant will receive a stipend payment of £500 to honour their knowledges, and will subsequently be invited to apply for up to £2,000 to cover costs to use the Community Health Impact Assessment Toolkit directly with their own community groups and members should they wish to.

-

The programme is led by Centric Lab and Clean Air for Southall & Hayes.

Centric Lab are prototyping ways to use health-based scientific evidence to support justice movements. Using neuroscience and environmental data to identify how biological inequity contributes to poor health outcomes in neighbourhoods and peoples that have been racialised and marginalised, they use this research to build open-access community tools, create new narratives and framings of health, and provide organisations with expertise and insights on health and place.

Clean Air for Southall & Hayes (CASH) are a grassroots community group from west London fighting for their rights to clean air and challenging the role that urban planning and governance structures play. They came together under the belief the air in their streets, homes and schools is being poisoned by the redevelopment of the Old Southall Gasworks, where the soil has been found to contain benzene, a carcinogen, and other harmful chemicals. Since the Berkeley Group began work on the site in Southall, they’ve had to live with a suffocating petrol-like odour and many people have reported breathing difficulties, chest pains, cancer and other symptoms consistent with chronic exposure to benzene.

Together we are long term collaborators with a history going back to 2018. We were awarded a feasibility grant by the Community Knowledge Fund in late 2022 to explore what designing a Health Impact Assessment from the community out looks like. In September 2023 we were awarded further funding to expand the process to other groups across the UK under the vision of “supporting ideas that use the knowledge in communities to address challenges that matter locally”, with the aim of allowing community groups “to play a stronger role in research and innovation” and “help develop and test new ideas and approaches to creating, sharing and using the knowledge held within communities to make progress on local and national challenges.” We’ve combined these resources with those from Impact on Urban Health to run a programme in 2024.

-

The programme is designed for people who are part of place based organisations concerned with the stewardship of their local area. For example, we expect to welcome people from Tenant’s Residents Associations, Community Land Trusts, Neighbourhood Forums. As such it is likely that people joining will hold a deep knowledge of local government and urban development policy, politics and practice. We believe that this shared knowledge base will make for a powerful and focused co-learning experience. We expect to welcome a group of 10 participants on behalf of their community organisations from around the UK.

-

The programme will be conducted remotely and is likely to run over a number of months. Subject to feedback from applicants we would all meet once in the evening’s per week or fortnightly for 8 sessions via Google Meet (which is free to join and requires no downloads). During this period there will be regular catch-ups, support sessions and “office hours”. There will also be support and guidance from stakeholders such as people from local authorities, health departments, and urban development.

We are aiming to start on Weds 24th Jan with the following schedule:

Session 1 - Welcome session

Session 2 - Exploring democracy and urban development

Session 3 - Equity, susceptibility and understanding different scales of impact

Session 4 - Ethical use of data

Session 5 - Sustainable Development

Session 6 - Solidarity, Kinship and Communality

Session 7 - Engaging with “the system”

Session 8 - How to use the Toolkit

Please note, to receive the second phase funding grant participants will need to attend at least 6 of the 8 sessions and with their best intentions contribute meaningfully to the sessions.

-

The end result will be a scientifically and practically informed community led HIA. This document and methodology can be integrated into Neighbourhood Plans or recommended to local authorities and development related stakeholders to be used in Local Plans and/or Supplementary Development Guidance.

-

We will run this programme with high safeguarding standards, ensuring that everyone feels comfortable to participate and contribute, free from intimidation, abuse, or neglect. If you join the programme a full welcome pack will cover the programme practice guidelines and ways of working together. This is in place to ensure that as we work together as people for the first time we are all benefiting from each other’s wisdoms, kindness, and intelligence. This programme is co-learning and collaborative, throughout we will welcome discussions about what we can offer throughout.

-

Use the online form at the bottom of this page. If you need any assistance please contact us via chiat@thecentriclab.com and will arrange a time to speak. The deadline for applications is 6pm Monday 8th January.

-

Despite many overtures of ‘community engagement’ the UK falls behind similar societies such as the USA and Canada in the collaborative design of health impact assessment work. This programme offers the chance to be a foundational step in community-led knowledge shaping local government policy, rather than merely responding to it!

We believe that community participation in HIA links up to the value system of a democratic and egalitarian society. Moreover, it has the potential, in addition to its other goals, to contribute to health promotion. Community participation in HIA contributes to policies that, building on local knowledge, and engaging target groups, address issues that are important, for these groups - in ways that are locally acceptable and appropriate.

— Lea den Broeder et al, Community participation in Health Impact Assessment. A scoping review of the literature (2017)

Community Health Impact Assessment Workbook

This justice-led toolkit is designed to support grassroots community groups co-producing a community informed Health Impact Assessment (HIA). This toolkit is designed to be used by grassroots organisations without the interference of domineering authorities. This is to give space and time for people to imagine a way something could be done, rather than being shoehorned into what’s permitted

This workbook is intended to guide grassroots and community oriented organisations through a series of exercises to create their own CHIA.

-

This guide is for people who are looking to build a vision for health in their neighbourhoods and communities. This workbook is designed to help facilitators go through a process that combines lived experience, world-building, and determinants of health analysis. This helps map out potential partners and stakeholders for long term impacts to health in the face of change.

-

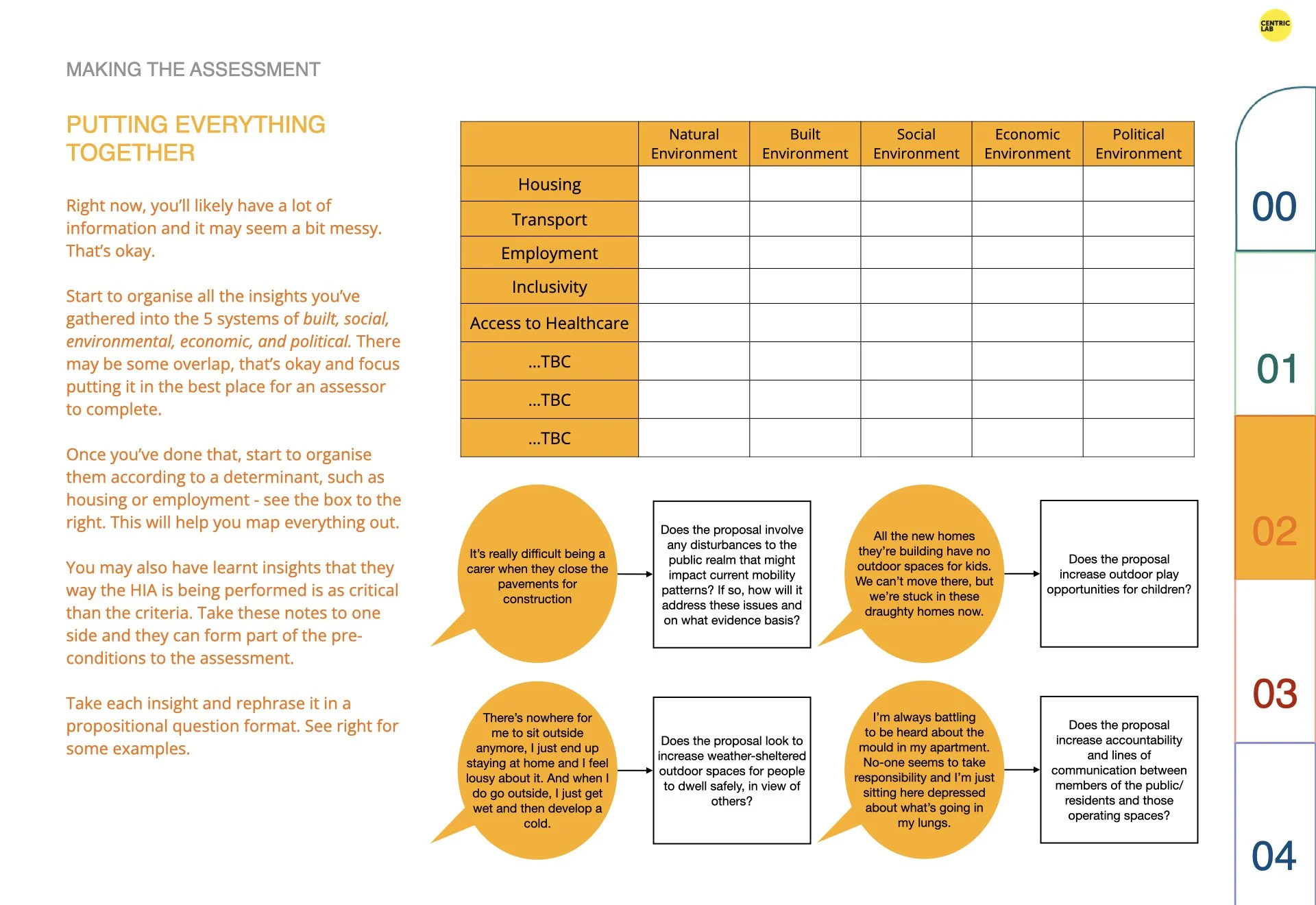

A community health impact assessment is an approach to harnessing the knowledge held within communities around how systemic injustices create health outcomes. It provides a practical approach to ensuring that a justice-led and systems based approach to judge the potential health effects of a policy, strategy, plan, programme or project on a population, particularly on vulnerable or disadvantaged groups are considered.

-

When a group of people are looking to have more representation and accountability to their lived experiences and conditions. This can be done as a field-building process that brings people together to form a vision and unite under a common banner. It can also be done when a large change is coming; such as a big brownfield regeneration project or even asking the question “what would the impacts of climate change be on our community?”.

-

For successful facilitation of this process we highly recommend you complete the online learning programme called ‘Introduction to Ecological Health’. It will help you become more informed about health as it covers issues around the histories and uses of data, ethics, and science in health. This workbook then helps you go through a step-by-step process to produce your own health impact assessment that another person can complete and consider all the variable factors that make up people’s reality of their health in the places they live, work, and play.

This roots of this workbook are in our collaboration with Clean Air for Southall & Hayes. Since 2018 we have been working alongside the grassroots group in their efforts for health justice. This workbook is the result of a project we explored together when towards the end one person said “we should share this process with others like us, everyone should have this opportunity to advocate for their health in this way.” Please consider supporting all grassroots groups near you. They are the lifeblood of change.

You can read a peer-reviewed journal article on our journey and methodology here.

To access the workbook please fill in the form below

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU

If you download the workbook we’d love to hear from you about your experiences. We can also offer advice and support.

p.s. to save the pdf to your computer choose a print as pdf or save as option from your computer.

Further Reading

Our Community Health Impact Assessment

This Community Informed Health Impact Assessment has been designed, reviewed, and consented by C.A.S.H. for use by others like us. It is intended to ensure that all considerations towards people’s health is taken when reviewing potential impacts as a result of construction or a new urban development. It has been designed in good faith to allow for effective, intentional, and important dialogues happen between communities like ours and those looking to make changes in our neighbourhoods.

Centric Lab & Clean Air for Southall & Hayes are sharing their CHIA.

It is the result of our collaboration and is being shared to support and inspire others.

Members of Clean Air for Southall & Hayes campaigning in their local area.

Our experience has been that the trickle-down nature of turning NGO guidance into local government policy has resulted in vested interests influencing the approach and outcomes of such guidance.

This can be evidenced by poor health outcomes resulting in the people of Southall from the overt levels of brownfield development sites.

The current HIA methodology fails to recognise the susceptibility of communities like ours who have experienced chronic and disproportionate exposure to physiological and psychological stressors from the places where we live and work and our histories as marginalised and racialised people.

Had health science informed systems been in place it would have noted the high risk to stress related health on the people of Southall, namely the emitting of carcinogenic chemicals from contaminated land at the former gasworks site

This Community Informed Health Impact Assessment has been designed, reviewed, and consented by us for use by others like us. It is intended to ensure that all considerations towards people’s health is taken when reviewing potential impacts as a result of construction or a new development. It has been designed in good faith to allow for effective, intentional, and important dialogues happen between communities like ours and those looking to make changes in our neighbourhoods.

— Clean Air for Southall & Hayes